A couple of weeks ago, I was lucky to spend some time in Cambridge, Massachusetts, attending seminars at MIT and Harvard. (That’s one off the bucket list). While there, we had the opportunity to attend a fascinating panel discussion on possible futures of how AI will shape the future of work. I was particularly thrilled that the panellists included Ethan Mollick, one of the best commentators on AI, and Daron Acemoglu, author of an incomparable history of technology. This blog post builds on that discussion…

The state of AI in the workplace today

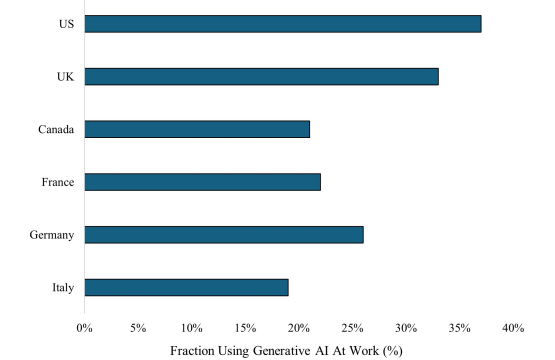

Before considering the future of work, let’s briefly consider how generative AI tools are being used today. A recent review of the labour market by economists at Stanford University [1] shows that in most developed economies, between 20% and 40% of workers currently use generative AI tools.

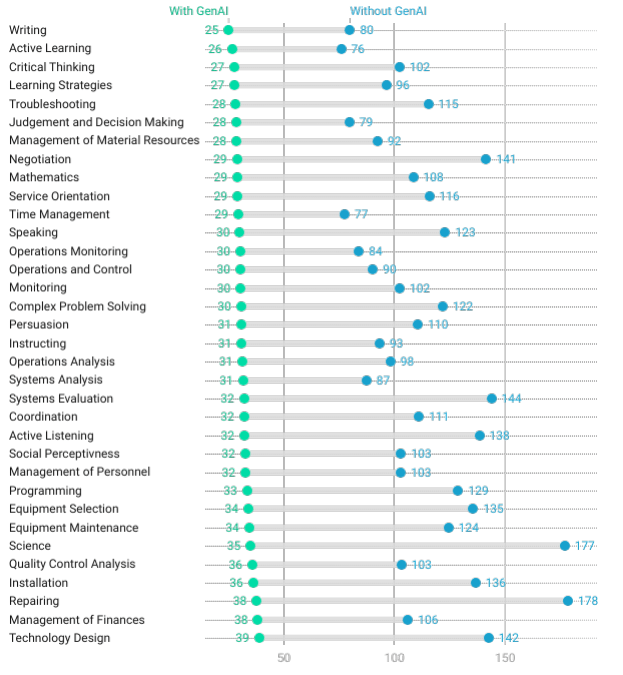

What is more striking is the impact AI is having on carrying out individual tasks – something we can refer to as “micro-productivity”. This report highlighted the impact on tasks across many disciplines, from writing to technology design, management of personnel and many more. The time cut to carry out these tasks was reduced by between 2.5 and 5 times over their unassisted duration.

It is therefore clear that while AI may not (yet) be replacing most human jobs, it is certainly being used to automate individual tasks at a significant scale. The report states finds “limited evidence that Generative AI exposure significantly affects job openings or employment levels.”This is consistent with my findings in a previous blog, which showed that while there are productivity gains experienced by individual workers, most companies are not experiencing these gains at the enterprise level [2]. In the seminar, Mollick argued, quite convincingly, that practically everyone is quite clueless about how to capture value or productivity. The big Frontier AI labs are ‘simply’ in a headlong race to produce the largest models tasked at performing best across a range of AI benchmarks in the quest to be the first to achieve AGI. The premise is that this is a high-stakes, winner-takes-all race. Mollick claims that to these labs, how these models will integrate in the workplace is a secondary concern.

In the enterprise, there is no established playbook for achieving AI-powered success, although there is broad experimentation. Companies will need to be fundamentally rewired to benefit from AI agents forming a core part of their workflows, rather than simply automating workflows designed for humans. We are still in the infancy of this process, and it’s occurring in pockets, such as in support centres and in software development teams. A report by McKinsey [3] states that across most organisations, agentic AI adoption is still in the pilot phase, with less than 10% of firms currently scaling AI agents.

Stating the obvious – AI continues to get (much) better

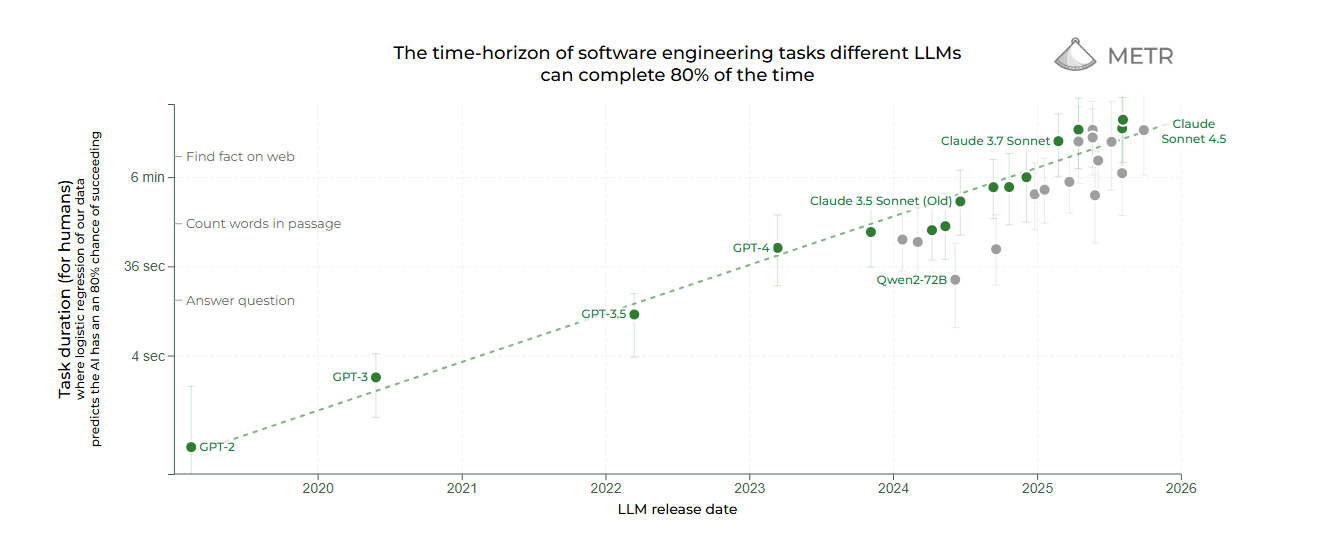

As this blog is supposedly about the future of work, rather than its present, where are we heading to? I will start by stating the obvious – AI continues to get better. Most models are updated every few months, with generational changes (e.g. GPT-4 to GPT-5) roughly on an annual basis. Strikingly, these improvements currently continue to be exponential in nature. Although AI systems routinely outperform humans in specific tasks such as reading, this is not sufficient to fully automate a human job. In practice, the jobs carried out by humans consist of fairly complex tasks, each of which is a long chain of smaller steps. To be able to fully replace that human, an AI agent must be able to carry out this long chain of tasks at an acceptable error rate.

To give a sense of where we are with AI viably replacing a human workers, consider research [4] coming out of METR, an organisation that assesses AI frontier models. This suggests that the task length that LLMs can carry out reliably [i.e. with >80% success rate] is doubling approximately every seven months. In 2022, GPT 3.5 could only carry out tasks which would take a human software engineer ~10s to carry out (with 80% accuracy). By 2025, ChatGPT-5 had shown sufficient improvements to carry out 26min worth of work at 80% accuracy. If AI systems were to continue on the current improvement path, a somewhat speculative assumption, then by late 2027 to early 2028, AI systems can successfully complete tasks equivalent to a software engineer’s whole working day.

How AI changes the value of work

Given that AI is already replacing tasks across a wide range of professions, what is the impact on the value of (human) labour, and hence the likely effect on wages? A recent paper by Seb Murray [5] describes why automation is not always bad for workers. The key finding is that if automation removes the simpler parts of a job, the work that remains often requires more expertise, consequently demanding a higher premium. Conversely, where automation impacts the more skilled parts of a role, wages will fall. Consider accounting clerks and bookkeepers. As spreadsheets took over the more manual parts of their roles, they evolved into financial analysts. Over the period 1980-2018, the number employed in these roles fell by a third, while salaries rose in real terms by nearly 40%. On the other hand, taxi drivers used to rely on deep local knowledge to navigate urban areas. London taxi drivers needed to pass a test called “The Knowledge”, which typically took three to four years to master. Yet Uber’s navigation software has largely nullified the value of this know-how, seeing taxi wages drop by between 30-60%.

So applying this to the advent of generative AI, we can extrapolate that in the absence of policy interventions, there can be a broad range of outcomes for different professions, both in terms of the numbers employed, as well as upon their wages. We can postulate that, for example, customer support staff with deep technical know-how of their products can easily be replaced by AI agents that have ingested the technical datasets and knowledge base of their products.

Learning 1. Combine domain expertise with AI savvy

So what suggestions can I offer to whoever is worried that AI may replace their job? Once again, I will rely on the AI adoption within software development as a preview of AI’s broader impact on the workplace. Andrew Ng, a serial AI entrepreneur and expert, explains how the most effective software engineering hires are those who combine an understanding of software engineering fundamentals with the practices required to construct AI applications (such as prompting, RAG, agentic workflows, etc.) [6]. He says experienced software engineers who retain a pre-2022 way of working risk becoming obsolete. Similarly, less experienced engineers straight out of college who don’t have a strong understanding of computer programming fundamentals have limited utility. Whether this means that newly-minted graduates are over-reliant on AI is unclear. There is anecdotal evidence on X that startups are avoiding hiring new grads for this reason. As Ng puts it, “without understanding how computers work, you can’t just ‘vibe code’ your way to greatness.”

The general lesson for the AI-augmented workplace is that unless your job is fully automatable, then you need to understand how best to augment your job with AI. This means understanding how to combine your own domain-specific expertise with an understanding of how GenAI tools can help you. This is true whether your skills are in the creative arts, commercial skills or engineering. Whilst I am not qualified to comment on the likely macro-economic outcomes, if we look at the impact robotics and automation have had on manufacturing jobs in the US and Europe over the past twenty years, there are much fewer jobs, though better paid. As the rather tasteless joke about the two runners who bump into a bear goes, you don’t have to outrun the bear; you have to outrun your friend. Though this advice is clearly not conducive to teamwork!

Lesson 2. Optimise AI for problem-solving and skills development.

And in terms of advice for those designing AI-enabled workplaces, it’s worth returning to the MIT seminar I opened this blog post with. Much of the debate was on whether the nature of AI’s impact upon work is pre-ordained or inevitable. Zana Buçinca, a researcher at Microsoft, argued that there isn’t a single foregone conclusion on how AI will impact work and skills. [7] This, instead, will depend on how AI systems are integrated into the workplace. Buçinca suggested that systems that are designed solely to fully automate activities (i.e. simply to optimise for the immediate business outcome) can degrade the human operators’ expertise over time.

The risk of deskilling is a much-researched topic in the field of medicine, where an over-reliance on AI can see an erosion of clinical skills [7]. This mirrors what has been seen in aviation for many years. An over-reliance on autopilots and automation has been linked to a decline in pilots’ manual flying and monitoring skills. The US Federal Aviation Administration consequently issued guidance to ensure that pilots regularly practice manual control. The conclusion is that AI-assisted systems should be designed not only to best automate and optimise the task at hand, but also to optimise the human experience, particularly cognitive engagement. For example, she suggested that systems that offered an AI recommendation together with a contrastive option as an alternative resulted in better outcomes than systems that made single recommendations. They also stimulated better and deeper human engagement with the AI assistants, indicating that chatbots do not offer a one-way trip to deskilling.

In my view, organisations’ long-term interests lie not only in the most effective short-term optimisation, but in nurturing and developing the bedrock of skills required to maintain the integrity of the profession. As professions such as law and management consultancy now rely on AI systems to carry out research previously assigned to junior associates, AI tools in the workplace must therefore be designed to help the professional development of workers. The alternative is a world where the integrity and know-how of entire professions risk being eroded in the long term.

Conclusion on the Future of Work

In a nutshell, I am really not quite sure what the future holds, and please accept my apologies if you feel let down by the lack of a bullish oracular prediction. I am fairly confident about a couple of things, though. First, as companies figure out how to design their workflows to integrate autonomous AI agents as well as AI-augmented workers, they will eventually see the productivity gains that have eluded them so far. As these changes take place, many jobs will go the way of bookkeepers, typists, and many office jobs of decades gone by. Those that remain will be AI-augmented in one way or another. The key discriminator for each job will be whether AI will replace the most complex tasks we carry out, or whether it will relieve us of the burden of the mundane and repetitive parts of our jobs. As AI systems become more deeply integrated into organisations’ workflow, the only way for organisations, and indeed society, to sustainably maintain and build the human skill base is to design AI systems that optimise the human experience, as well as the business outcome. While this may sound obvious, this does not appear to be the state of play today.

References and Further Reading

Hartley, Jolevski, Melo & Moore, The Labor Market Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence, SSRN #5136877, working paper, last revised Oct 2025

Mollick E., “Making AI Work: Leadership, Lab, and Crowd”, One Useful Thing, May 2025.

Singla A., “The state of AI in 2025: Agents, innovation, and transformation”, QuantumBlack AI, McKinsey, November 2025.

METR Blog, “Measuring AI ability to complete long tasks”, March 2025, updated on October 2025.

Murray S., “A new look at how automation changes the value of labor”, MIT Management Sloan School, August 2025.

Ng A., “AI skills are redefining what makes a great developer”, Deeplearning.AI, September 2025.

The post AI and the Future of Work appeared first on The Sand Reckoner.