Niels Bohr famously said that making predictions is hard, especially about the future. So I am definitely not going to set off on a fool’s errand and try to figure out what lies ahead in 2026 from an AI perspective. I will, however, consider the themes that may be significant as the world navigates the implications of wide-scale adoption. These views are, as always, my own, although I will draw on observations made by others, adding links for further reading.

Now with an (AI-generated) companion podcast. Give it a try.

In this post, I explore what may happen to AI demand (a rather obvious outlook) and the resulting implications for the evolution of AI compute and data centres. I then touch on a favourite topic of mine - AI interpretability and explainability (and their limits), and whether this will have any impact in the roll-out of properly autonomous agentic workflows.

1. Jevons Paradox. A model for AI demand?

In a recent blog, Aaron Levie, the CEO of Box, argued that AI adoption will follow the pattern known as Jevon’s Paradox. William Stanley Jevons was an English economist at the time of the Industrial Revolution. He noticed that improvements in the efficiency of coal use drove up demand for coal, rather than decreasing it. Where output is constant, the use of more efficient technologies should reduce the demand for raw materials (e.g. making cars more fuel efficient). However, it also reduces the cost or barriers to entry of using technology, and hence demand instead increases.

We have seen this pattern numerous times, such as the transition from mainframe computers to PCs, the adoption of faster Internet connections and the availability of cloud computing. All these technologies not only made existing processes more efficient, they were also intrinsic drivers of brand new ways of using the technologies. Faster Internet did not just mean quicker email; it created the online gaming and streaming industries.

Levie is highly likely to be right that looking at AI demand through the prism of existing use cases is to miss the point. AI agents will dramatically lower the barrier to entry to the automation of non-deterministic tasks. Earlier this year, Stanford economist Erik Brynjolfsson explored the implication of Jevons Paradox. He argued that for some professions, productivity will be transformed, which will result in lowering the cost of their output, which in turn will increase the demand to the lower prices offered. It is the last point that is critical. Take the case of software developers. If their productivity increases 10-fold, will this result in an explosion in demand for more software development? Time will tell. What it certainly will do is shape how AI compute is structured.

Read more:

Levie, Aaron. “Jevons Paradox for Knowledge Work.“ LinkedIn, December 28, 2025.

• Rosalsky, Greg. “Why the AI world is suddenly obsessed with a 160-year-old economics paradox.” NPR (Planet Money), February 4, 2025.

2. What Training / Inference Mix are we heading towards?

The growth in AI data centre construction is straining industries as diverse as construction, energy supply, AI chips, networking equipment, and most recently RAM. Much of the attention has been focused on the demand required by frontier labs such as OpenAI to develop and train the latest generation of AI models. However, AI model training is only half of the AI compute mix, with the other half being inference - i.e. using AI models to solve the tasks assigned to it.

The mix of AI workloads matters -a lot. Training of large frontier models makes use of enormous data sets (at least hundreds of terabytes) and several millions of compute hours of high-end GPUs to create models with trillions of parameters. This is what has been driving the adoption of the highest-performing GPUs, as faster processors and larger clusters shorten the model training, experimentation, development and validation time. These workloads are large, complex, and require a lot of orchestration. They are typically bursty as the AI labs pass through different phases of their development.

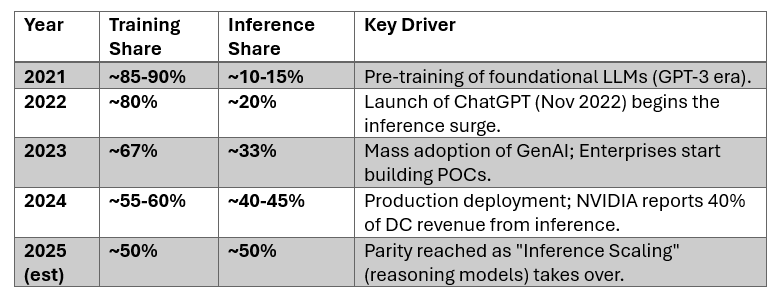

However, as the AI industry begins to mature, the compute requirements for AI usage (i.e. inference) will overtake the demand for training. Already, reports by McKinsey and Deloitte estimate that global AI compute usage is roughly split 50/50 across compute and inference. The dynamics of inference compute are very different to training. When solving an AI task, what is important is latency (i.e. the round-trip time to process a query) and cost. Therefore, inference workloads are characterised by billions of small requests, creating a lot less bursty traffic profiles, optimised for user experience.

So what are the implications of this? As companies will seek to shift from growth to sustainable profits, cost and latency will be the two driving factors to enable them to scale as more efficiently as possible. We are therefore likely to see a split in hardware towards GPUs optimised for large-scale training loads, and hardware optimised for real-time, low-latency inference loads.

The early stages of the generative AI boom has been optimised for development speed - how fast can the frontier labs develop, train and optimise their models and gain an edge on their competitors. Training clusters are therefore optimised for very high levels of parallelism and cluster-scale efficiency in order to train very large models, with networking and memory capacity also optimised for highest bandwidth operations possible. Similarly, as training typically operates in very large batches, reliability is a key concern. On the other hand, inference fleets run continuously, as they pool together requests from a very large number of users. They are therefore optimised for cost per token, which means high concurrency, utilisation efficiency and optimising power consumption.

This mix matters as it will shape the compute mix in future AI data centres across NVIDIA-style GPUs or Google-style TPUs, and where the data centres are located - whether closer to where power is available or closer to where the user is.

Read more:

Stewart, Duncan et al., “More compute for AI, not less.” Deloitte Insights, November 18, 2025.

Arora, Chhavi et al., “The next big shifts in AI workloads and hyperscaler strategies.” McKinsey & Company, December 17, 2025

3. Will AI become more explainable?

At heart, modern generative AI models are non-deterministic ‘black box’ systems. In other words, the output for a given input (e.g. a prompt) will be different each time the model is run, and it is not possible to work through the internal reasoning. This is due to the inherent structure of the most generative AI models. Individual concepts or pieces of data are not localised in individual areas of the AI model, such as a neuron or parameter, but are instead spread in connection patterns across large numbers of parameters. Furthermore, modern AI systems are multi-layer (or multi-step) systems where the final output is produced by a long chain of intermediate non-linear steps. This means that it is intractable in practice to work backwards through the ‘reasoning’ process, or even to work back to the source training data that contributed to the response. In a nutshell, AI systems are typically “emergent” rather than designed, so that their inner workings are difficult to understand.

Why does this matter? First, for any high-stakes application, such as safety-critical applications, health applications or where there are large financial implications, even a small number of mistakes can be harmful. The very fact that you cannot explain how a system came to make a decision is a blocker to its adoption on legal, regulatory or ethical grounds. Similarly, the opacity of models means that there is no way to detect if the models or their training data have been tampered with maliciously, meaning that it is difficult to trust them. The core question is that as the capabilities of AI systems continue to improve, the risk implications of their lack of explainability will continue to grow. For example, how can we check if an AI is being devious?

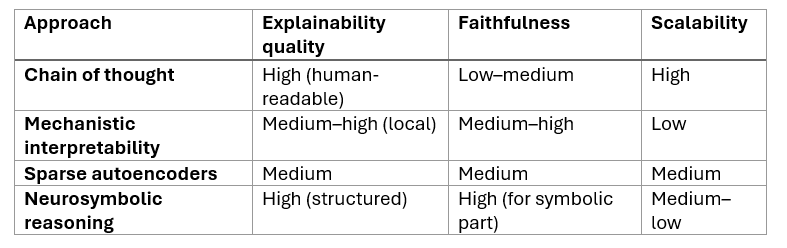

In a way, we are beginning to make some progress. “Chain of Thought” (CoT) processing, which involves AI systems decomposing problems into a sequence of prompts, can give indications on the approach taken to solve a problem. e.g. “scope the problem, search for references, categorise and remove duplications, etc.” Howeve,r the inner workings of each individual step remain obfuscated.

Much current research focuses on mechanistic interpretability, in other words, mapping the internal connections of the model. Other promising approaches, such as the use of Sparse Autoencoders - i.e. decomposing groups of neurons that activate on many features to maps of neurons that activate on individual features- are starting to be applied to large LLMs. [see below for a description of how they work]. The third main category, called neurosymbolic reasoning, combines neural-network-based learning with logic-based reasoning. Whilst the neural parts remain a black box, these models have applicability in constrained, rules-based applications.

In a nutshell, while 2025 has seen some breakthroughs in interpretability and explainability, no approaches have yet made it into mainstream LLMs, due to a combination of intrinsic model architecture constraints and cost efficiency. It is clear however, that the demand for solutions in this space will only continue to grow, particularly as AI systems are allowed to act more autonomously

Read More:

Dario Amodei, “The Urgency of Interpretability”, April 2025

4. How should we manage autonomous AI?

2025 has seen the first implementations of AI agents - where AI instances have some autonomy in the tasks they carry out. Probably the space where their use is most widespread is in software development, where tools such as OpenAI’s Codex software development agent and GitHub Copilot Workspace are seeing AI tools take on a greater share of tasks across the software development lifecycle. However, we are still in the very early stages. A survey published by McKinsey in November found that less than 10% of large firms are scaling the use of AI agents in any given function. So while adoption of AI is growing, it is predominantly driven by individual workers using it as an assistant to carry out their individual tasks.

To be clear, the direction of travel in the development of AI agents will result in AI-enabled systems that can observe, plan, act, respond and iterate over prolonged periods with limited human interaction. When AI is used as an assistant, there is, by implication, always a human in the loop. However, in agentic implementations, humans are no longer implicitly within the workflows, a shift from the Copilot Model to the Autopilot Model. This can have a number of implications.

First, coming back to Jevons’ Paradox, we truly enter the territory of exponential growth. We are already seeing implementations in systems consisting of easy-to-characterise rules such as customer support centres, enterprise workflow and finance operations. As the technology becomes more accessible, we will see agentic deployment in a broader range of business functions. The incremental cost of adding a new agent will be low compared to the potential benefits of adding one more agent - certainly a fraction of the cost of a human worker. Companies that manage to master multi-agent orchestration will gain a compounding advantage. They will therefore have a strong incentive to deploy as many agents as technically possible. The possibility therefore, exists of an explosion in size of agentic systems.

This will likely change the nature of work, with more roles dedicated to oversight and supervision of AI agents. We are all familiar with the “span of control” problem when managing human workers. How many AI agents can a human reasonably be responsible for? What about humans supervising AI agent supervisors? This will have significant implications for organisational design - teams responsible for managing interactions between agents, monitoring interactions with external systems, suppliers and customers, as well as teams responsible for oversight, monitoring and audit.

From my perspective, as human workforces are augmented by growing agentic AI work, there will be a corresponding shift to interactions and traffic being driven by AI systems rather than by humans. This means that APIs and endpoints designed for human interaction will instead be used by autonomous agents. We are already seeing web platforms being overwhelmed by AI use. The low incremental cost is already giving rise to “Agentic Sprawl”, and this will likely accelerate, both in terms of traffic internally within enterprises (e.g. between different enterprise applications) as well as with external parties.

Bringing it all together

I wasn’t quite sure where this blog post would lead me, but I feel that all themes here are interrelated. For all the talk about agentic AI systems, rolling out agentic workflows that span across multiple functions in a business will require a redesign of those workflows to be tailored around AI agents rather than human workers. This will be a non-trivial technical and workplace design challenge, not least due to the explainability limitations of current AI models. However, should these problems be solved, then we can expect a truly Cambrian explosion of AI agent adoption.