This weekend, Geoffrey Hinton, who pioneered the field of deep learning and one of the so-called ‘godfathers of AI’, gave a wide-ranging interview to the Financial Times [1] (link behind a paywall). In it, he painted a rather gloomy picture of how AI is going to change the world. He said, “Rich people are going to use AI to replace workers. It’s going to create massive unemployment and a huge rise in profits.”

We should treat these words with caution. It is well-known that experts tend to over-emphasise the importance or impact of their space. Nevertheless, you’d be hard-pressed to find any serious technologist or economist suggesting that AI will be anything other than disruptive. Like many parents, I wonder how to prepare my teenage kids for the uncertainty that lies ahead. More specifically, in this blog, I have a look at how well the UK higher education system appears to be preparing our young people for this change. Note that I am not an educator, nor claim any expertise in pedagogy, so treat these musings with healthy scepticism.

A Tale of Two Time Horizons

We can apply two very different horizons to explore the disruption AI will have on our economy. If we were to take a very long view, AI offers to radically bring down the economic cost of productive output, particularly amongst knowledge workers. In itself, this is nothing particularly novel. The advent of agriculture displaced foraging (so-called hunter-gatherers), bronze and iron tools displaced stone tool-making, the invention of the printing press made the skills of monastic scribes largely redundant, the invention of steam-powered weavers saw the onset of the industrial revolution, while mass-production in the 20th century saw skilled artisanal labourers replaced by less-trained factory workers. In all these transitions, overall economic output increased, though at the cost of (often significant) hardship for those workers who lost their jobs.

If we then zoom into the onset of generative AI, we can see that timescales of change collapse to a handful of years. It is the speed of change, rather than its impact, that is truly revolutionary. For example, ChatGPT (based on GPT 3.5) was launched in November 2022. This year’s cohort of computer science graduates were already well into their first or second year of undergraduate studies when ChatGPT launched AI into mainstream discourse. At the time they were selecting university courses, the majority of these students would have been oblivious to the pending arrival of gen AI, yet by the time they graduated, they were facing a very different job market.

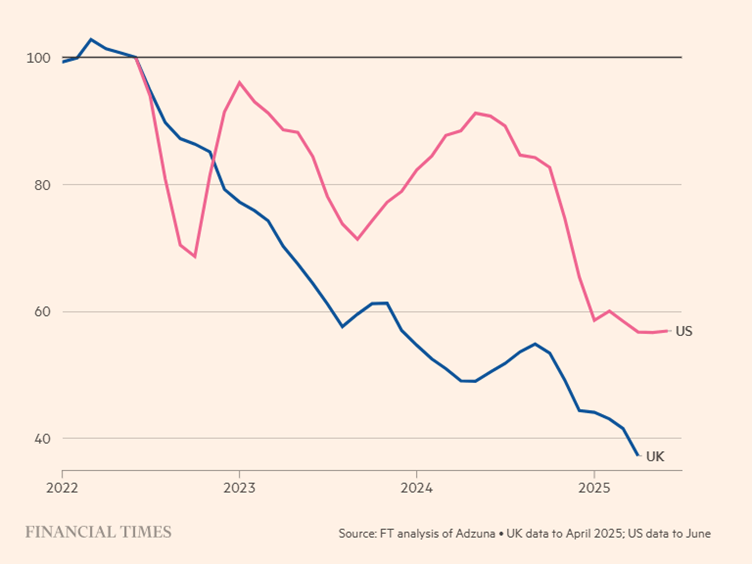

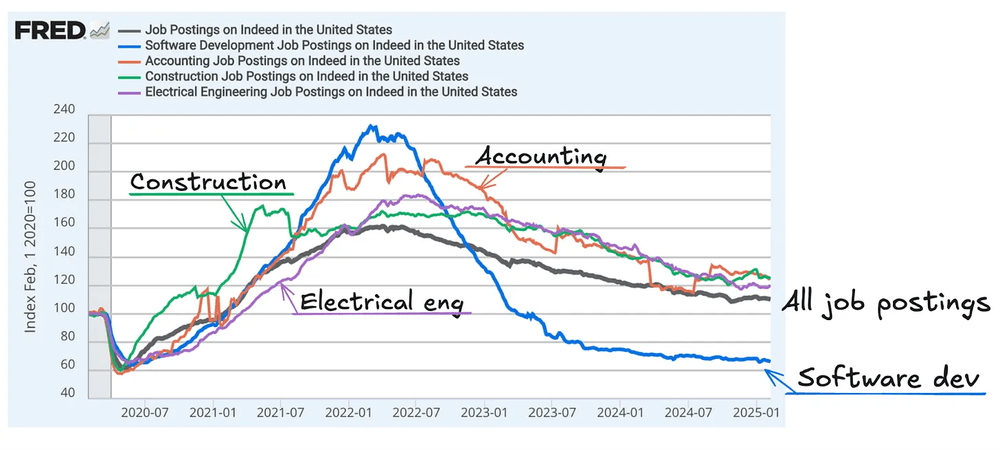

Graduate hiring in the UK and US has plummeted over the last three years [2]. A separate study by McKinsey, shows that the reduction in hiring was twice as acute in jobs more exposed to AI compared to those with low exposure [3]. The point is that the displacement in occupations took a couple of generations at the time of the Industrial Revolution. This time round, that disruption may take as little as five years. Yes, we have seen this seismic disruption before (or at least, humanity has). What is new is the speed at which it is taking place.

The hollowing out of entry-level jobs

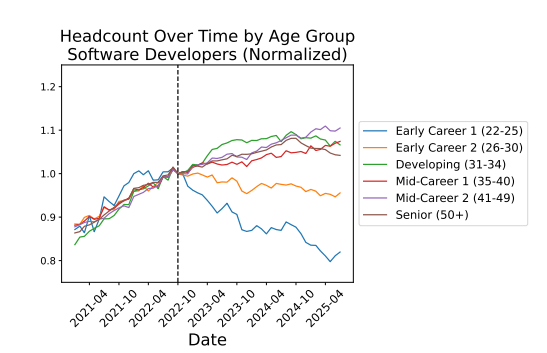

A paper [4] by researchers at Stanford University, helpfully titled ‘Canaries in the coal mine’, studied payroll data of 50 million workers in the US. The study found that employees aged 22-25 in AI-exposed occupations were 13% more likely to lose their jobs than others in less-exposed jobs. As I explored in my previous blog, entry-level software engineering jobs, which involve component-level programming, debugging, testing and documentation, can easily be replaced by generative AI tools such as coding copilots. The study attributed much of this job loss to areas where AI can automate work (i.e. replace a human worker), rather than augment (i.e. help a human worker) the work. In an op-ed in the New York Times, the Chief Economic Opportunity Officer (what a job title!) at LinkedIn describes [5] how the bottom rungs of the career ladder are disappearing. Outside tech jobs, legal firms, consultancy companies, retailers and so on are all now looking towards AI to take on duties once carried out by entry-level roles.

Looking Ahead – what does this mean for graduate jobs?

Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic believes this trend will accelerate. In an interview with Axios [6] he explained that Anthropic research shows that while AI models are primarily being used for augmentation, he believes that over the next two years, their use will tip more and more towards automation.

So just think about it for a moment. This will happen 1-2 years before this year’s university undergraduate intake enters the job market. At the beginning of the year, Mark Zuckerberg said that in 2025, “AI will be effectively a sort of mid-level engineer that you have at your company that can write code.” Coming back to Amodei, he believes that AI will replace half of entry-level white-collar jobs in the US within five years, increasing unemployment to 10-20%. For context, a shift of 10% in unemployment represents a loss of 17 million US jobs, which dwarfs the approximately 6 million manufacturing jobs lost in the US through globalisation of manufacturing.

UK Universities Spring into Action. Or do they?

As I mentioned previously, I have a busy autumn ahead, visiting a host of Russell Group Universities (supposedly the best universities in the UK) with my son who is hoping to start an engineering degree in a year’s time. Surely, these august, world-leading institutions, home to the country’s best technology thinkers dedicated to moulding and nurturing the technologists of the future would have this challenge in hand?

You will therefore understand my surprise that, having sat through about ten “introduction to engineering” courses, covering mechanical, aerospace, automotive and electronics disciplines, not once did I hear anything about AI. Of course, they were all happy to talk about their wonderful facilities, their co-curricular opportunities, their partnerships with industry, and the sheer excellence of their academic credentials. But with the notable exception of a talk on a B.Sc. in Artificial Intelligence course, not a peep on AI.

So, given that AI is undoubtedly going to transform most technology roles, does this feel adequate? My previous blog suggested that all engineers will effectively become supervisors of AI, be they by using AI tools as part of the design process, optimisation, prototyping, experimentation or validation. All engineers will need to be adept at their domain of expertise, as well as in the use of AI and data. Yet none of these universities sought to mention anything about it.

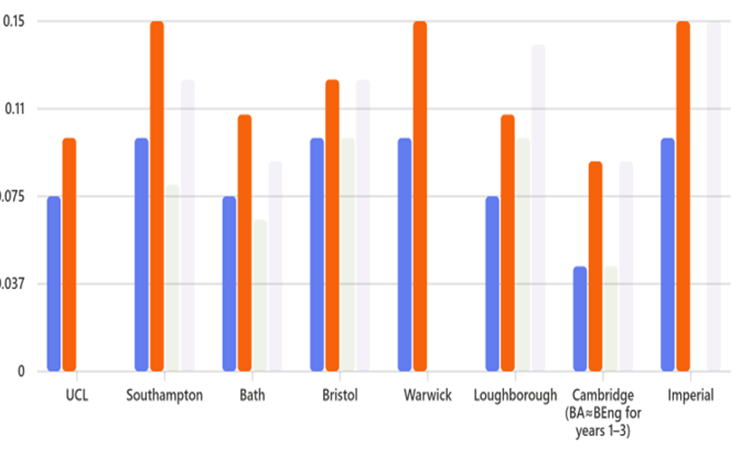

I then headed over to the undergraduate prospectus web pages of the same universities and asked ChatGPT to assess the curricula for engineering degrees for subjects related to data science and AI. I selected mechanical engineering-related courses as these are technology specialisms where data and AI do not traditionally feature heavily. On looking at the data, you can see that AI typically appears as a ‘specialisation’ subject in the latter years rather than a foundation for the course. This takes the guise of subjects such as control theory, machine learning, robotics and mechatronics. For this reason, 4-year MEng courses tend to have nearly double AI/data content of 3-year MEng courses. There are exceptions, though. Southampton offers a compulsory Data Science and Computing for Engineers in year, while Cambridge unsurprisingly offers a host of rigorous-looking options, with an early focus on Computer Science, followed by later options such as Probabilistic Machine Learning.

UniversityMechanical BEngMechanical MEngAerospace/Aeronautics BEngAerospace/Aeronautics MEngUCL6–9%8–12%——Southampton8–12%12–18%6–10%10–15%Bath6–9%9–13%5–8%7–11%Bristol8–12%10–15%8–12%10–15%Warwick8–12%12–18%——Loughborough6–9%9–13%8–12%12–16%Cambridge (BA≈BEng for years 1–3)3–6%6–12%3–6%6–12%Imperial8–12%12–18%—12–18%

Protecting Academic Integrity and the Learning Process

UK universities seem to prioritise the integrity of their qualifications above all else. This can be seen in “Russell Group principles on generative AI in education” policy paper [7]. This paper focuses primarily on addressing the risks associated with the use of Gen AI in higher education. Privacy, bias, inaccuracy and misinterpretation of results, ethics, plagiarism, and exploitation are all (quite rightly) highlighted as concerns. However, most universities provide thoughtful guidance on how AI tools (particularly Gen AI) can be used in to support learning as well as where and how they can be used to help create assessed work. Some even use these policies to ensure that students are ready for life in an AI-enabled world.

So what should Universities learn from this?

1. A University Degree is not a guarantee of anything.

Universities need to wake up and smell the coffee. Evidence is mounting that employers are increasingly not relying on a University degree or formal qualification as evidence that candidates have the required skills to compete in the new jobs market. A recent study [8] showed that while AI roles grew by 21% between 2018 and 2023, mentions of university requirements for these roles actually decreased over this period. Employers are prioritising skills over qualifications, clear evidence that universities have work to do to remain relevant.

2. Data, Statistics and AI as core subjects for technical disciplines

Especially for technical subjects, data science, statistics, and learning models should be treated as foundational subjects and not as specialisation options. There will be no technical field where some form of AI will not be part of the toolkit used by practitioners. Coding assistants as used by programmers represent just the tip of the AI-assisted revolution, which will reach all technical fields. Progressively, AI agents will take on the tasks of individual knowledge workers, so that each practitioner will effectively become a supervisor of AI agents. As such, they will need to be fluent in the language of AI – namely, data and statistics, as well as in the structure and methodologies used by the learning models. Key skills will be orchestration of models, managing multiple agents and being able to take professional accountability on their behalf through robust validation, particularly for high-stakes outcomes such as in health and safety-critical applications.

3. Basic AI Model Literacy for all disciplines

Some of the most professions most exposed to AI are those that traditionally fall into the humanities. A report by Microsoft into the most exposed professions sees interpreters at number 1 (perhaps unsurprisingly) and historians at number 2 (more surprisingly). A paper by researchers at Harvard Law School describes how AI can see productivity gains for lawyers in excess of 100 times, in one example, reducing associate time for preparing for litigation from 16 hours to 3-4 minutes. [9] Yet, reviewing the course material for five of the UK’s top law degree courses sees AI treated as part of “technology and law regulation” subjects, rather than a core part of the lawyer’s toolkit.

All knowledge workers should be equipped with an understanding of the characteristics, structures and limitations of AI models, particularly generative AI and other deep learning models. Their inherent non-deterministic nature combined with their propensity to hallucinate means that you’d have to be foolhardy to rely on the models without a thorough understanding of how they operate, at least conceptually.

4. Reinvent the value proposition

It is difficult to make predictions about such a fast-moving space, other than to say that such changes will continue for a while and will at times feel overwhelming. This means that Universities’ once-in-a-lifetime model of learning seems increasingly ill-equipped in today’s world. Just as the Open University pioneered distance learning fifty years ago, it is time again to be radical. Universities should shift towards offering long-term part-time learning models that accompany their students throughout their professional lives. Online learning providers such as Coursera, Udacity and Deeplearning.ai, all offer content from many providers. Universities should expand their partnerships with these providers – both making use of external content, as well as using these platforms to distribute their own lifelong educational offerings. Some Universities are already doing this. MIT has long been a leader in open AI programmes, and offers free online courses as well as certified qualifications through its MicroMasters programmes, with other top-tier universities also making courses available on platforms such as EdX and Coursera.

Predicting the future is hard

When assessing technologies close to the peak of the hype cycle, it is difficult to make predictions as to the extent of the disruption they will bring and how quickly they will be adopted. I wrote a piece back in 2018 on the inevitability of safe-driving cars, proof of the pitfalls of getting carried away with the excitement of ‘revolutionary’ technologies. Nevertheless, AI will very likely replace large chunks of what knowledge workers do today, radically reshaping their jobs in ways that are hard to predict. Ignore this at your peril.

References and Further Reading

C. Criddle, “Hinton: ‘AI will make a few people much richer and most people poorer’, Financial Times, 5 September 2025.

C. Murray, “Is AI killing graduate jobs?”, Financial Times, 24 July 2025.

Allas T., Goodman A., “Not yet productive, already disruptive: AI’s uneven effects on UK jobs and talent”, McKinsey & Company Blog, 14 July 2025.

Giridharadas A., “AI and the Vanishing Entry-Level Job”, The New York Times, 19 May 2025.

VandeHei J., “Behind the Curtain: A White-Collar Bloodbath,” Axios, 18 May 2025.

Russell Group, “Principles on the use of generative AI tools in education”, July 2023.

Couture R., “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Law Firms’ Business Models”, Center on the Legal Profession, Harvard Law School, February 2025.

The post What does AI mean for university education? appeared first on The Sand Reckoner.