I’ve been writing this blog intermittently for around ten years, exploring questions that intrigued me from a professional perspective. I started off exploring the then-emerging Internet of Things space in the early 2010s, during which time I took on roles building smart home and connected car products. Over the years, it evolved into a broader exploration of themes related to leading tech teams, while occasionally keeping an eye on advancements in machine learning and artificial intelligence.

In this blog post, the professional and personal coincide for the first time. As an engineer and leader of tech teams, I am very interested in understanding what the advances in artificial intelligence mean for how tech products will be built. On the personal front, I am currently visiting universities with my son, who is looking to start an engineering course. So the question as to what engineering will look like in five, ten, or twenty years is particularly pertinent. This blog is my attempt to explore that question.

A spotlight on software engineering

Software engineering is the technical discipline that to date has been most impacted by AI. At one level, the introduction of AI is simply extending the developer’s journey away from the native execution of assembly code, providing greater levels of abstraction, just as progressively higher-level languages have done today. However, LLM-based code assistants also fundamentally change the nature of coding. For the first time, they introduce a non-deterministic element, as LLMs do not create repeatable outputs. In effect, we are outsourcing control of the logic, the very essence of our intent, to machines.

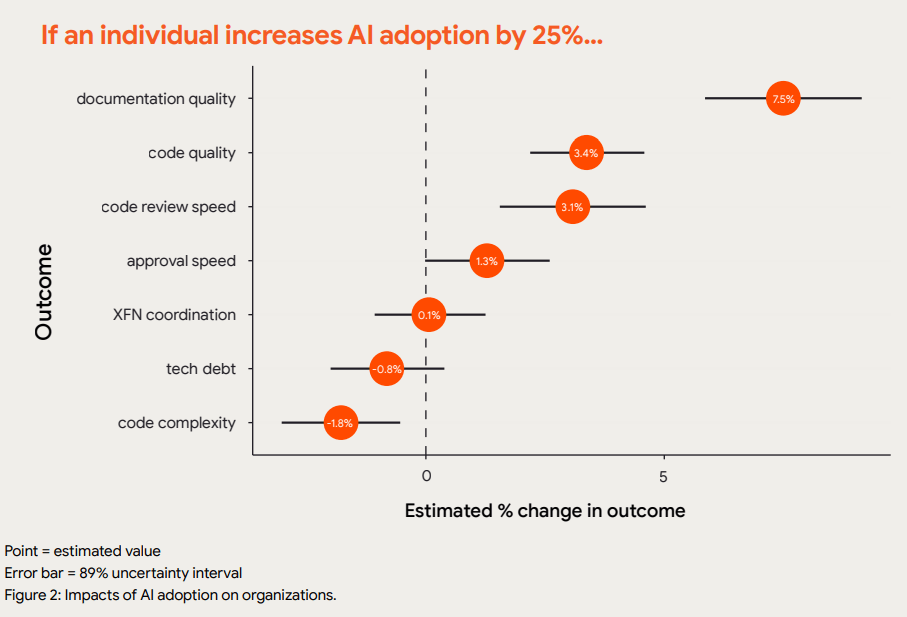

So what’s the impact of AI coding assistants upon the developer experience and overall productivity? Early research shows a mixed picture. A recent report [3] by DORA, the DevOps Research and Assessment team, describes benefits as seen by developers, including flow, job satisfaction and a reduction in burnout. However, the gains at an organisational level appear to be modest, with a 25% increase in a user’s AI adoption increasing productivity by only 2.1%. While the quality of documentation, code quality and code review time improved significantly, this came at the cost of an increase in technical debt and code complexity. These gains in productivity are mirrored by a randomised control trial of 96 developers at Google, which showed a 20-25% increase in productivity in coding tasks attributable to AI.

Overall, the real-world impact on productivity at the enterprise level appears to be mixed. The DORA report suggests there is negligible, if any, improvement in software delivery effectiveness. Another paper by METR (Model Evaluation & Threat Research), a body assessing frontier AI capabilities, found that for developers working in a large, mature open-source repository, task completion time increased by around 20%. It appears that improvements in coding productivity at the developer level are, to date, offset by increased load on oversight, review and integration.

Some insight into what’s going on can be found in the recently released, and rather excellent, annual developer survey by Stack Overflow [15]. Although 84% of developers now use AI assistants, only 3.1% of them highly trust them, and 46% actively distrust them to some extent. The two main bugbears are that “AI solutions are almost right, but not quite” (66% of respondents) and “debugging AI-generated code is more time-consuming” (45% of respondents).

Even though we are still in the early days of AI adoption in software development, some things stand out:

AI is fundamentally changing the nature of software engineering. AI tools are here to stay, and they are changing the nature of coding and of the software that is created. For example, AI tools create non-deterministic, ‘fuzzier’, less predictable codebases. They are lowering the cost of building code from scratch, reducing the perceived benefit of creating reusable, modular code. These are pretty fundamental shifts in what developers have traditionally valued.

New skills are required to master software engineering in the age of AI. Software engineers now need to master a blend of traditional software skills and AI competencies. These include prompt and context engineering, AI-assisted code review, AI output evaluation, integration into AI APIs, an understanding of AI model behaviour, and a new security and compliance paradigm. Successful developers and organisations will be those who invest in learning to take on these new skills.

This requires a mindset shift. As Gen AI models become more tightly integrated into coding tools, development pipelines and documentation systems, the boundary between human and machine contribution will blur, requiring developers to increasingly work with AI tools as a co-contributing partner, rather than as a traditional coding tool.

Organisational effectiveness gains are currently lower than expected. The use of AI is leading to higher overall coordination costs, as AI-generated code tends to require more discussion, review or coordination across different developers. Additionally, the current unreliability of AI systems requires greater investment in security, validation and compliance oversight.

The AI benefit is not consistent across all developers. Most of the research indicates that junior engineers, working on smaller components, can benefit most from AI assistants. This mirrors the way they would ask senior colleagues for help [5]. However, these are the tasks most easily automatable, so AI appears to be disproportionately impacting developers who are just starting their careers. For more senior engineers, with responsibility for a large, complex codebase, the opportunities AI provides are more limited. For example, randomised trials show larger gains in productivity for junior engineers (~27-39%) than senior engineers (~8-13%) [6]. The greater the scope, the more complex the problem, the more difficult it is to solve a problem without creating knock-on effects elsewhere.

AI does not (yet) offer tech leadership. Yes, AI can help with coding, but it does not yet act as a substitute for non-coding tasks expected from senior engineers, including the creation of complex design documentation, technology roadmaps, arbitrating with other teams, or simply providing your teams with the vision of the way forward.

And the broader learnings for other engineering disciplines?

Having cast a spotlight on software engineering, what are the learnings for other engineering disciplines? Software engineering lends itself particularly well to the use of AI, as it often operates in a ‘fully digital’ space, where all the inputs and outputs are digital. There are often (though not always) fewer safety implications than for physical engineering applications. How will this be different for real-physical applications such as manufacturing, semiconductor design or aerospace?

First, let’s not forget that AI has been used in engineering design for well over a decade. Be it in the form of image recognition and robotics on an automated assembly line, the use of machine learning to optimise engineering designs or carry out predictive maintenance, and in the use of digital twins to model real-world systems, learning systems are not new. The question is rather, what will be the effect of generative AI, and its inherently non-deterministic nature?

1. AI for initial concept generation

Let’s start at the beginning of the engineering process. Much as AI co-pilots can help blog authors suffering from writer’s block, generative AI is already being used successfully by many engineering firms in the meandering and seemingly random process of creating initial exploratory designs. The integration of LLMs into physical CAD software already allows for design concepts to be generated from natural language prompts at a much higher level of abstraction. For example, a paper by Byrne et al shows how LLMs can be used to provide CAD designs for multiple concepts for consumer products, in this case, headphone stands, by giving it instructions in natural language [10].

FlecheTech, a Swiss startup, uses a fine-tuned LLM to produce PCB [printed circuit board] prototypes for hobbyists, small companies and anyone who requires prototype designs, but lacks the in-house expertise to design it from scratch. FlecheTech claim that this reduces the time to create a working board from around 8 weeks to one week [15]. These are both examples where generative AI’s non-repeatability and variation are actually a strength, as it can produce multiple variations as designers explore early concepts.

2. AI for design automation

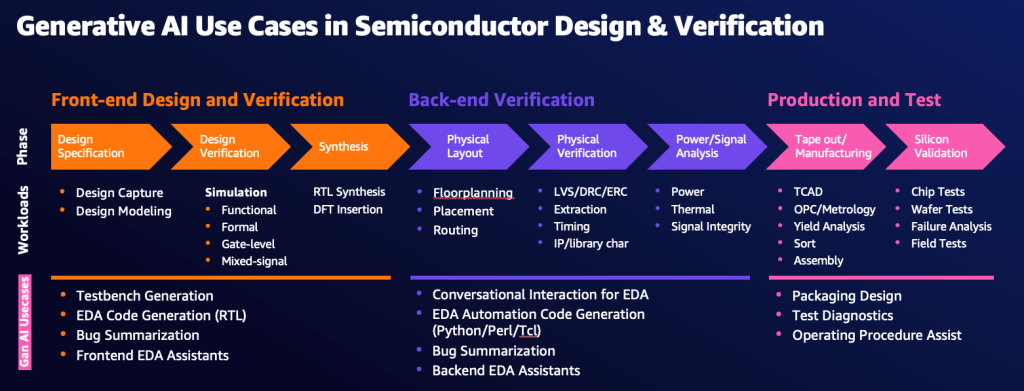

Early ideation occupies only a small proportion of the overall engineering development effort. If AI is really going to transform engineering, it is going to be in the more structured design and development phases. Consider semiconductor design, which for decades has relied on Electronic Design Automation (EDA) software as the only way to deal with the extremely high complexity of modern processors. Semiconductor design includes processes such as design specification, front-end design, physical design validation and test and analysis. NVIDIA estimates that up to 60% of a chip designer’s time is spent in debug or checklist-type tasks [11]. In fact, the hardware design process is not dissimilar to software development, as the chip designs are fully described in software. LLMs therefore have the same potential to design and optimise code and synthesise information as they do in the software development space, with leading EDA providers such as Synopsys already building generative AI capabilities into their tools.

There are several other examples of companies using AI to automate engineering processes. CloudNC, a British startup, is using AI to automate the process of programming CNC (computer numerical control) machines, which are the mainstay of precision manufacturing [14]. These machines cut metal to precise specifications required by industries such as aerospace and medical devices. Although CloudNC don’t disclose how their algorithms work, it appears to use a combination of AI-based training and physical geometry to determine the optimal cutting strategy. These examples show that, whilst not yet as pervasive as for software design, generative AI solutions are beginning to appear across multiple technology areas.

3. AI for complex engineering optimisation

One area where AI is already having a big impact in engineering design is in engineering optimisation – the process of developing and testing different designs to see which operates best in a given set of conditions. Traditionally, this has been a fairly manual process, and even when reliant on simulations, it is very computationally-intensive. Neural Concept, a Swiss engineering software company, has developed neural-network-based software to help Formula 1 teams create the most effective aerodynamic designs possible [12]. Formula One car development is a race in itself, with each team racing to create the most effective car package possible before and during a season. Neural Concept’s software helps create outcomes in seconds rather than hours, conferring a clear competitive advantage. Similarly, Airbus is making use of AI to create 3D printed structural components using generative algorithms mimicking organic structures. [17]

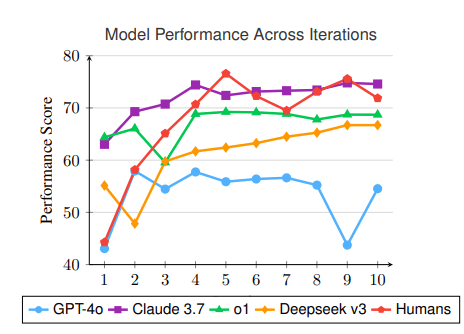

Recent research has also shown that the combination of reinforcement learning (RL) and LLMs can outperform engineering design as carried out by a human expert. A recent paper explored the use of commonly available LLMs, such as OpenAI’s GPT-4o and Anthropic’s Claude 3.7 to design a rocket that met a given set of performance criteria, such as achieved altitude, structural integrity and landing accuracy. The combination of LLMs and reinforcement learning was found to exceed the performance of an expert who has carried out similar rocket design tasks over many years.

So what does all this mean for the future of engineering?

Given what we have seen from how generative AI is being used in software development, and the examples in other engineering areas, some themes begin to emerge.

We have not even begun to scratch the surface. First, a caveat. We need to consider that it has been barely three years since LLMs emerged from their research labs, and their capabilities are evolving at breakneck speed. For example, this blog hasn’t considered the impact of agentic systems, or indeed of artificial general intelligence (AGI). That said, I am pretty confident that the lessons below will hold true.

Data really matters. AI-assisted systems can only work with whatever data they are provided with, be it in the form of data to refine or pre-train models, or feedback to guide their systems through reinforcement learning in tight verification loops. Therefore, no matter the engineering discipline you are involved in, you will need to be fluent in capturing, managing and processing data, not just design files, but real-world physical data, and ensuring that it is available for use with your AI-assisted platforms.

Understand the black box. When we use generative AI models, we are, for the first time, outsourcing the logic to a machine that we currently don’t fully understand. This issue, called the interpretability problem, means that it is critical that engineers at least understand the underlying limitations as well as the benefits of using such models. These characteristics include the tendency to hallucinate, difficulty in repeatedly creating consistent outcomes and an excessive sensitivity to how the prompts are crafted. The list goes on. They are undoubtedly incredibly powerful tools, but they come with significant downsides.

Oversight is critical. The time spent ‘engineering’ outcomes will shift away from developing and designing individual components or subsystems. These are tasks that, with the right instructions and data, can easily be outsourced to AI assistants. Instead, AI-assisted engineering will require greater emphasis on shaping and crafting the requirements, contexts, specifications, and other input data to be used by AI-powered tools. Similarly, it will be critical to invest in the oversight of outcomes, in other words, validation. This is to ensure that the system as a whole still works well (i.e. the system integrates correctly as a whole) and to ensure that safety, security and compliance requirements are not compromised. In other words, each engineer will effectively become the supervisor of their AI team.

Finally, domain expertise remains key. As I hope this blog has made clear, AI systems are only as good as the context that they are provided with. Without a specific and clear context, AI systems can produce great outcomes that either don’t solve the problem at hand or fail to work in their intended environment. This means that the engineer’s insight into what is really needed to succeed in a given context is critical. This engineering input, or tasking, could take different forms. It could be the requirements upon a component or sub-system for it to work well in a broader system, or the features or capabilities will meet the customer’s needs.

Finally…

Writing this blog post has been a bit of a journey, and the key learning for me is that engineering is becoming simultaneously more complex, but also much more exciting. Used well, AI tools can turbo-charge the creative potential of individual engineers. However, human engineering judgement will remain as critical as ever. Engineers will need to be multi-disciplinarians, mastering both their domain of specialism as well as the fundamentals of the AI models they use.

Finally, while I tried to write about the future of engineering, what I ended up exploring was, in effect, the present and near future. I have not even begun to consider the implications of systems of AI agents interacting with each other has upon how technology development is carried out. That, my friends, is a topic for another day.

References and Further Reading

Sergey Tselovalnikov, The LLM Curve of Impact on Software Engineers, February 2025

Martin Fowler, LLMs bring new level of abstraction, June 2025

DORA, Google Cloud, Impact of Generative AI on Software Development, v.2025.2

DORA Research, Helping developers adopt generative AI: Four practical strategies for organizations, March 2025

Becker J, et al, Measuring the Impact of Early 2025 AI on Experienced Open-Source Developer Productivity, July 2025

Walsh D., How Generative AI affects highly skilled workers, MIT Sloan School of Management, Nov. 2024.

Anthropic.com, Anthropic Economic Index: AI’s impact on software development, April 2025

Neural Concept Blog, AI in Engineering: Applications, Key Benefits, and Future Trends

Rizwan Patel, The Future of Engineering belongs to those who build with AI, not without it, VentureBeat, May 2025.

Byrne et al, Application of Generative AI technologies to engineering design, 12th CIRP Global Web Conference, 2024

Singh K. et al, Generative AI for Semiconductor Design and Verification, AWS Blogs, March 2024.

Stevens T., How Neural Concept’s aerodynamic AI is shaping Formula 1, TechCrunch, April 2024

Simonds T., LLMs for Engineering: Teaching models to design High-Powered Rockets, arXiv:2504.19394v1, April 2025

Kahn J., Can AI help America make stuff again?, Fortune, June 2025.

Tucker M., When Generative AI meets Product Development, MIT Sloan Management Review, Fall 2024.

Autodesk Press Release, Autodesk and Airbus Demonstrate the Impact of Generative Design on Making and Building, November 2019

The post How AI is changing engineering appeared first on The Sand Reckoner.