Over the years, I have been lucky enough to have held engineering and product roles across very different companies. I have worked in industry sectors as diverse as energy, automotive, big tech, consumer devices, and most recently, government. If I have learned one thing in this journey is that context is everything. What works for one organisation may not be the best fit for a very different one. For example, the product and engineering practices required to produce a highly integrated product, such as a car, are very different to those required to create fully digital experiences such as a streaming video service.

So it is with this mindset that I have approached my most recent challenge, taking an organisation with a very strong engineering ethos operating within the UK national security space to become more of a product organisation. What works at Amazon does not transfer unchanged to a very different cultural and operational context. In this blog, I distinguish the core principles behind what I call ‘the product mindset’ from the practices and processes. The mindset should be applicable to most scenarios and contexts, while the practices and processes will vary according to the organisation. Many change programmes focus on the latter - talking about artefacts, ceremonies, roles, job titles and so on. They are all important, and indeed, essential. But let’s strip that all away and explore what really matters.

Also available as an (AI-generated) podcast. Give it a go!

Engineering Excellence and the Product Mindset

So, what is a ‘product organisation’? For people who have only ever worked in product organisations, including every tech company out there, this may feel like a self-evident question. A bit like a fish trying to imagine a world that is not full of water. This question does however provide useful a useful framing. One alternative to a product organisation is the engineering organisations, of which there are two main flavours.

The first are “the tasked builders”. These companies create engineering outputs to meet the designs and requirements of their customers. Typical examples include ODM (original design manufacturers) who create consumer products to specifications provided by well-known brand. Examples include suppliers to aerospace manufacturers who create components for use in an aircraft, or a software supplier creating a bespoke piece of case management software for a government application. These companies are characterised by a strong ‘specification’ based way of working and optimise for meeting specifications rather than for end-user outcomes.

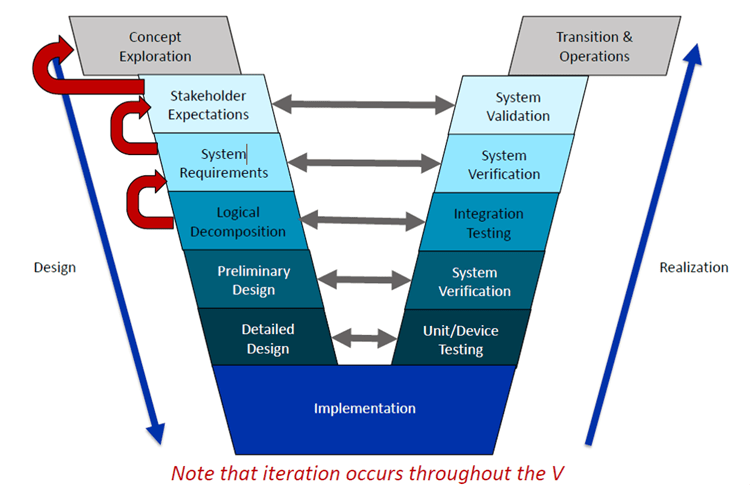

The second are “the systems builder”. These are companies that own their outcomes, which they directly monetise. They operate in a largely linear fashion from a set of specifications defined at the outset. In these companies, uncertainty is managed through detailed up-front modelling, engineering design and specification rather than through customer feedback. Many such organisations follow the “systems V” approach. Here, top level specifications are first created. What follows is a typically one-way decomposition into smaller components which are implemented, and then progressively integrated and tested as the final product is realised. This approach is common in large engineering organisations such as nuclear power, defence contractors and large construction companies where the intended outcomes are typically well-understood.

Figure 1: The Systems V Model. Source: NASA [1]

What is the Product Mindset?

To be clear, I am not suggesting that there is anything intrinsically wrong with being an engineering organisation or following a ‘Systems V’. Often it is the right approach for the problem at hand. For example, creating a nuclear power plant does not lend itself well to an iterative ‘trial and error’ approach. These examples are however helpful as they help bring into sharp relief what I mean by a ‘product company.’

In my mind, a product organisation has two main characteristics. First, it wholly owns and is responsible for the entire lifecycle of its products. There is no doubt that most well-known tech brands such as Apple to OpenAI in the consumer space, to Shopify and Salesforce in the business tech space, as well as countless non-tech brands such as Coca-Cola, McDonalds, Zara and Nike fully own their products and related customer experience from cradle to the grave. However, ownership of the product, and all its implications upon a company’s brand is not enough. Product organisations are accountable for every stage of the product lifecycle — not just initial design or post-launch support, but from ideation through delivery, operation, evolution, and ultimately decommissioning. Customer experience is not a phase; it is a continuous constraint on decision-making.

Given this framing, let’s have a look at what I consider to be the main characteristics of product organisations.

1. A product is for life, not just for Christmas

The main units of delivery of engineering organisations are ‘projects’. Let’s dissect what these are. According to the Association for Project Managers, the UK’s professional body for project managers, a project is a “a unique, transient endeavour, undertaken to achieve planned objectives.” [2] Consider the word transient. This defines a project as having a beginning and an end, of interest only while the ‘endeavour’ is underway.

This contrasts with the product approach, which is to take responsibility for the product outcomes and customer experiences as a continuous process, from inception through to end-of-life. This lifecycle view is typically captured in a product roadmap – where all the products and experiences are mapped against a timeline. The product manager’s responsibility is to understand and manage today’s products, learning from them to create tomorrow’s experiences. They are always balancing whether to invest in new features or products or to enhance those products already in use.

The culture of the company often plays a strong influence in where priorities are applied. At Amazon, for example, “operational excellence” activities, aimed at making the service more robust, improving availability, were always at the top of product backlogs, reflecting a belief that availability is the most important customer feature.

Tesla represents a great example of this characteristic in action. Most car manufacturers traditionally took a product engineering approach – with distinct project teams responsible for designing and developing cars to the point of manufacture, as opposed to supporting them in-life. For Tesla, the software is always being updated and evolved, so that the car you experience today is different from the one you bought. It is always being kept up to date.

While the project ends at the point of delivery, a product manager’s responsibilities do not. At Tesla and Amazon, the in-life experience is not someone else’s problem, such as an outsourced operations team. Product managers remain responsible for the experience for as long as there are customers using their products. It is genuinely a responsibility for the entire product life.

2. Obsess about outcomes, not outputs

Project managers focus on outputs, often defined through the triangle of cost, quality and time. While these remain essential building blocks of any time-defined project, product organisations measure success against customer-impacting metrics.

Amazon, amongst other companies, distinguishes between input and output metrics [3]. Input metrics are things that you wholly control and can influence outcomes. They are ‘leading’ (i.e. ahead of the fact) indicators of success. Output metrics are the customer-impacting consequences. Taken together, metrics represent the ‘mental model’ behind each product, the hypothesis that links the thing you do (e.g. a slicker user interface) with the intended outcome (e.g. more customer usage and enjoyment).

For example, an input metric for ChatGPT could be the speed of response, or latency. This is (largely) controllable by OpenAI in terms of the design of the LLM, how many tokens it can input and process. Fast responses should result in a higher likelihood of continued usage, driving up their output metrics, such as the number of weekly users, number of subscribers, subscription renewal rates and app store reviews.

The focus on outcomes is crucial. It forces product teams to be close to their customers, not only during the initial concept and design time, but throughout the life of the product. Delivering a project on time, to spec and budget while important, is only a means to an end. What really matters is understanding if your product is being used and is delivering the intended benefits. Tracking and managing usage is used as an input to refine the product, thereby nudging the input metrics in the right direction, in turn improving the customer experience or enjoyment of the product. Designed well, your input and output metrics will provide a strong feedback loop by which to improve the product experience.

3. Iterate, Iterate, Iterate

If metrics are important signals on how well your product is doing, then equally important are the actions you take in response to those metrics. This is where feedback loops are critical. If you cannot take timely action in response to a metric that is not moving in the direction you hope for, then that measure is simply a ‘vanity’ metric.’

The use of rapid feedback cycles is one of the defining characteristics of a product organisation compared to the ‘systems builder’ organisation we described earlier. This approach is not limited to digital or software experiences, characterised by the “move fast and break things” stereotype. Take the satellite rocket launch industry. Typically, these were highly risk-averse companies fully adopting the systems engineering methodology. Their approach to risk reduction (a critical consideration given that a rocket engine is essentially a controlled explosion) is through the detailed and meticulous design and specification process. All engineering design takes place up-front, with extensive use of computer modelling and simulation. This leads to the specification of all the subsystems and components that comprise the rocket. The aim is to use rigorous engineering early in the design process to meet rigorous reliability and safety standards.

SpaceX on the other hand, optimised for a much more frequent launch cadence, aiming to use each launch as a means for optimising and improving the experience [4]. By accepting the possibility of failures as part of the learning process, SpaceX engineers are able to get real-world product data much earlier in the development process than engineers in legacy contractors. Over the longer-term it is able to converge to the same level of reliability as its competitors. SpaceX’s philosophy is to simplify the design, focus on the essentials, and learn by doing. The Falcon 9, developed according to this approach suffered some early mission failures, but went on to have close to 600 successful launches since its introduction in 2010 [5]. By comparison, its competitors Lockheed Martin’s Atlas V Arianespace’s Ariane V managed just over one hundred launches each.

Figure 2: Rapid product iteration – SpaceX booster re-entry

The key learning here is to treat each product iteration as an experiment, with the expected impact upon chosen metrics as the hypothesis being tested. The feedback frequency determines the learning rate. Even an unsuccessful product iteration can then lead on to success. The earlier you can get real world data, the quicker you learn and produce products that delight your customers.

4. Focus on problems, not specifications

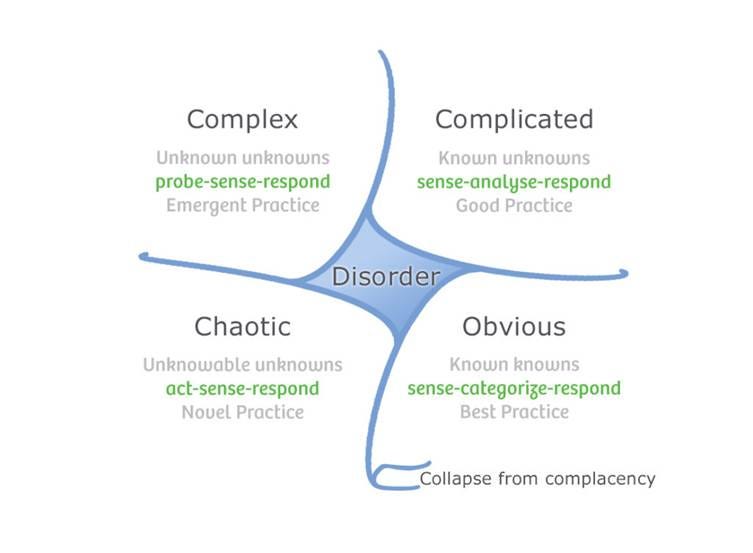

Perhaps the biggest cultural difference in moving to a product way of working is the change in role of product specifications. Consider the ‘systems’ approach described earlier. This is optimised for ‘complicated’ problems – i.e. problems where there is a known relationship between cause and effect – where problems can be analysed and decomposed. Creating many sophisticated engineering products falls into this category – for example bridges, power plants. In this model, risk is reduced by specifying the solution up front.

Product approaches are optimised for complex problems, where it is difficult to predict the impact of your actions in advance. Often this is because the end-user has a say in how they react to your product, in other words, the outcome is influenced by end user adoption and behaviour. Many national security problems fall in this category as they are influenced by the behaviours of adversaries or threat actors. For this reason, product management shifts the emphasis away from up-front specification to back-end learning. Through a probe-sense-respond cycle, you are reducing risk through controlled experimentation.

Figure 3: The Cynefin framework of problem types

This is why user stories have become embedded in the day-to-day practice of product management. Describing intended outcomes as product statements, in the form of, “as a user, I want to … so that …” is designed to shift the engineering process to start with the end problem in mind. This may seem like a minor shift, but it is utterly fundamental to the whole product approach. First, it encourages the product manager to focus on the fundamentals. Having spent a fair few years as a systems engineer specifying complex consumer products, I have played my part in what I call the tyranny of specifications.

Consider the smartphone industry before the advent of the iPhone. Nokia were in pole position to be the dominant player. They had a fantastic supply chain, a dominant market position, Europe’s strongest brand, and all the right technology components, including, in Maemo OS, arguably a better operating system than either iOS or Android. [6] While there are many strands to the story of Nokia’s demise, one contributing factor was a lack of focus. Nokia was encumbered by trying to implement all the legacy requirements that all the previous generations of phones. So rather than exploit the characteristics that made the new touch-screen smartphones different, Nokia were constrained by thousands of requirements from mobile operators who bought their phones. Apple, on the other hand, under Steve Jobs’ visionary leadership, launched a phone with a very limited feature set, but with great user experience. By focusing on a clear vision for the end user experience, rather than what the mobile operators were asking for, Apple upended the mobile phone market.

SpaceX adopt a similar philosophy, which is referred to as their “first principles” approach [7]. Rather than asking themselves, “how are rockets usually built?” they focus on the fundamentals, which in the case of space rockets is the intersection of physics and economics. This way of thinking manifested itself in the design of their Merlin engine (no relation to the eponymous Spitfire engine) which was designed to be simpler, less complicated, but able to be manufactured at scale much more cheaply than existing engines. Similarly, by designing fully reusable rockets, they challenged the industry norm that reusability was too complicated a problem to be practical.

Focusing on the essence of the problem at hand allows product managers to identify what is essential, or core, to the product. Every requirement has a cost or requires a trade-off. Adding requirements that don’t improve the core user benefits will often undermine the product. In the case of space rockets, they can add so much cost that they undermine the business model, or in the case of smartphones, complexity can ruin the product experience and compromise reliability and launch timelines.

5. Innovate on behalf of the customer

For this principle, I will directly lift a phrase originally attributed to Jeff Bezos. [8] This is a belief that in order to meet customer needs, companies often need to innovate and create products or experiences that their customers are not expecting. To me, the philosophy is that the accountability for coming up with the best solutions for customer needs lies not with customers, but with product teams. As the probably apocryphal story goes, Henry Ford once said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

Let’s consider a few examples. We are all familiar with the Dyson bagless vacuum cleaner, but when James Dyson invented the use of bagless cyclonic tech [9] to capture and manage dust, customers were preoccupied with having cheaper bags and more constant suction. No-one was asking to dispense with bags altogether. Similarly, Netflix, when still a DVD rental company, recognised that the underlying customer need was not for cheap and efficient DVD delivery but for convenient home entertainment. As broadband internet was rolled out across the US, Netflix created a streaming platform that transformed the global media landscape. And for a more personal example, when I led the team that created the Wiser Heat smart home heating system at Schneider Electric, our insight was that people control their lighting cheaply on a room-by-room basis, so why couldn’t they do the same for heating?

It is important to be clear that I am certainly not advocating that product teams ignore customers and work in an ivory tower. To the contrary, you can only innovate really effectively if you have a really intimate knowledge of the customer problem set. There are different ways this can be achieved. Palantir, which started off as a defence and intelligence software product company, achieves this through use of forward deployed engineers (FDEs) who are embedded with customer teams to help feed back customer needs into the core product development [10]. This approach contrasts with the traditional software integrator model where embedded teams create bespoke software solutions for their customers.

6. When platforms are products

Sometimes answering the question “what is the product?” and “who is my customer?” is not straightforward. Let me elaborate. Imagine you are designing a range of electric vehicles. You will need to bring together a whole host of complex systems together – the battery and charging system, the suspensions and ride control, the powertrain, the infotainment system and so on. If you are producing more than one vehicle, it would be prohibitively expensive to design each of these subsystems to be specific to the need of each vehicle model. Economic reality dictates that you will need to reuse some of these components. In effect, the subsystems I mentioned are now platforms, supporting multiple applications (in this case different vehicles), and your immediate customer is the vehicle programme.

Choosing when to create a bespoke solution for a single product, also known as vertically integrating your product, or whether instead to create a reusable (or horizontal) platform is one of the core challenges product teams face. Vertically integrated solutions can be tailored to the needs of a single customer but doing so can be prohibitively expensive. Additionally, solving similar problems many times over creates increasing complexity. On the other hand, horizontal platforms, whilst offering the opportunity of economic reuse, also come with the risk of creating excessively complex solutions that meet no problem well.

The spin-out of Amazon Web Services (AWS) is the archetypal story of a set of enablers becoming products in their own right. Originally developed to support Amazon’s online retail offer, it was spun out as the first public cloud platform. This effectively turbo-charged the mobile app industry, as start-ups no longer needed to make expensive capital investments in computing infrastructure. Similarly, Google’s internal cluster orchestration product, Kubernetes, became a de facto standard way for managing software containers across multiple industries.

However, platforms are not limited to the software space. For example, the EV electrical and software architecture of the EV manufacturer Rivian has been productised and is the basis of a partnership with Volkswagen. In turn, they are offering the EV platform to other manufacturers. Industry segments as diverse as smartphones, car architectures, aero engines, satellites all make use of shared platforms to support multiple products.

Entire volumes have been written on platform design, and I will not delve into that literature here. What matters from a product mindset perspective is recognising when a subsystem has become a product in its own right, with its own customers, trade-offs and lifecycle. The central challenge is not technical, but conceptual: understanding who the platform is for, what problems it is meant to solve repeatedly, and where reuse begins to erode rather than enhance customer value.

Be wary of transformation anti-patterns

When adopting a product mindset, there are some common pitfalls that need to be avoided. Here are three that stand out.

1. Product in name only

The first is to adopt the lean/agile artefacts and ceremonies such as standups, scrum teams, quarterly planning, roadmaps, job titles, and so on, while leaving the underlying product development philosophy unchanged. This is the “engineering remains the same” fallacy where an existing way of working is simply wrapped up in new language. There are a couple of hints that this is what may be happening. First, your budgetary responsibilities and cycles remain unchanged. True product organisations devolve key product decisions, including resourcing (money and people) to product organisations. If your financial planning cycles are unaffected by your move to product, and your accountabilities have not changed, the chances are that your transformation has been largely cosmetic.

2. Product ‘paint by numbers’

The second main pitfall is to adopt a product model straight out of a textbook, with no consideration of the context it is being applied to. Every context is different. The existing organisational culture, the nature of the relationships with customers, the network of partners and suppliers will all influence the transformation journey. Any product model that does not adapt to this reality will struggle to take root.

For example, consider applying this to an organisation with a strong engineering heritage. The product mindset offers engineering teams great latitude in applying their engineering judgement. This includes how best to defining platforms, where to innovate on behalf of their customers, or the opportunity to pare back a problem to engineering first principles. In other words it can place stronger emphasis on engineering fundamentals, further burnishing the engineering culture. Alternatively, where an organisation already has an established reputation of brand and product excellence, this can be further reinforced by the product mindset. The product way of working brings greater focus to the organisation’s core value proposition. It reinforces the discipline of prioritisation, distinguishes what is core from what is distracting, while at the same reducing the gap between user problems and development teams. Taken together, this approach further enhances the organisation’s existing offering.

3. Ignore the whole system impact

The final major pitfall is to consider the product teams as an isolated ‘bubble’ ignoring the organisation-wide implications. This is true for both ‘front office’ as well as ‘back office’ functions. For example, digital transformations that generate true value are those that substantially enhance the customer offering. Organisations as diverse as IKEA, HMRC, the UK’s tax office, Domino’s Pizza and the Spanish Bank BBVA all used product-led transformation to re-imagine their customer offering for the digital age.

Similarly, you will be unable to shift to more agile and experimental ways of working if your back-office services are not also reconfigured to be compatible with your new ways of working. If your commercial contracts are still based on up-front specifications with risks transferred to the suppliers, or if delivery lead times are measured in months. The same is true for your risk and financial governance. Do your oversight mechanisms reflect your new approaches to managing investment and risk?

A final thought – Context is everything

So hopefully this piece has given a sense of what I consider to be core to the product mindset. As a final thought, I’d like to reiterate that this is not a collection of prescriptive rules or a recipe book but is instead a set of guidelines that underpin the product way of working.

As I mentioned previously, context is everything. These principles should be applied sympathetically to the context and culture of your organisation. Most organisations are pretty heterogenous. They consist of a mix of different cultures, product offerings, functions (e.g. logistics, supply chain, manufacturing, professional services etc.), skillsets (specialists, managers, sales and business development, finance and so on), markets and customers. This heterogeneity requires considerable judgement to navigate. Different parts of your product portfolio may need to be treated differently. Similarly, the implications will be different across your different business functions. #

No-one said this was going to be easy!

References

Palantir Blog, “A Day in the Life of a Forward Deployed Software Engineer”

Berger E., “Liftoff, Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days that Launched SpaceX”, Collins, 2023

Clear J., “First Principles: Elon Musk on the Power of Thinking for Yourself”

European Patent Office – James Dyson, the bagless vacuum cleaner